I’m not a motorcycle collector, I’m a mechanic and a rider, and I have been for almost 60 years. As such, I’ve accumulated some great motorcycles. That doesn’t mean I have bikes hanging from the ceiling or on display. That means I have bikes waiting for me to get off my ass and do something with them. I didn’t “collect” a single one. I accumulated them with the thought of riding the wheels off them. For most of them, I did exactly that.

I’ve decided to sell some, and that’s a BIG problem because I won’t sell them needing a bunch of work just to run and drive. So I have to do all the shit I meant to do many years ago before I let them go.

“Let them go” is a carefully chosen phrase. I don’t need the money, and I don’t even need the space. They could sit here in my shop gathering dust until I kick the bucket, and it will not affect my balance sheet, my workflow, my happiness, or any other factor other than one irritating little issue–they should belong to someone who has plans for them.

I don’t.

The plans don’t need to be daily driving–some of these bikes are not simple to ride, though oh my lord, do they ever make you feel young and turn some heads. But it would be cool if they do get ridden. If you haven’t ridden a Goldstar at speed, you are missing one of the iconic thrills of motorcycling. The only thing sillier, or more fun, is a Vincent at speed, and that’s only because your ass is hanging out 500cc’s further. They can’t stop on a dime as modern bikes do, so thank god Goldstars handle like a ballerina wearing track shoes.

You also probably don’t want to do anything showy anywhere where there are police in earshot. The sound of a Goldie backing down through its Twitter “muffler” feels like a stiletto up your spine. Even if you haven’t done anything wrong, the gendarmes will notice you.

The worst part about prepping these bikes for sale is that I’m falling in love again. But I’m resolute. They can’t continue to rot in my shop. They’re going.

First on the block is my 1956 BSA Goldstar Pseudo Clubman. Let’s get something straight about DBD Goldstars, if you’re thinking this would be a nice bike to take trips on or to commute in style–forget it. These were among the highest performance, fastest bikes on the planet in the 50’s. Literally, there was no question of that. It was a different time, and in 1956, if you had a Goldstar and could handle it, you were the real deal. You could do the ton, and more, and you could do it in places where other people couldn’t.

It was undeniably fast. Accomplishing that with a 500cc single with 1950’s technology means that every aspect of these bikes is there for performance with the bare minimum of creature comforts. You can draw the wiring diagram in less than a minute. Headlight, tail/brake light, generator, battery. No key, no fuses, no turn signals, no heated grips, and certainly no electric starter. Brutal, purposeful, temperamental, uncompromising, and crazy fun on a twisty road when you don’t have to be anyplace special at some specific time–but you like to get there fast. That’s why I bought it and why I rebuilt it to suit me. I wanted to enjoy empty country roads and pretend I’m lapping at the Isle of Man. That engine sound bouncing back from the trees, and the insane gibbering of the twitter exhaust whenever you back down for a corner is something no other motorcycles can deliver. It worked, it was great fun, and then I got busy with other bikes and race cars, pushed it into the lineup of other bikes in my shop, and put the dust cover on it. Fifteen years later, it’s time for someone else to have some fun with this thing.

This is the real deal–DBD.34.GS.3346. That weird number means everything to Goldstar freaks. Goldstars were produced from 1938 to 1963. but to a purist, a Goldie means a DBD34 produced between 1955 to 1963. All Goldstars shared the same frame–350cc or a 500cc, Catalina, Clubman, Roadster, or Daytona–same frame with a few different bits bolted on and different ratios in the transmission. It’s all about the motor, and the DBD 34 is THE motor, hand-assembled by experienced engineers who selected the bits for best fit and performance and then dyno-ed every bike. Literally–every single Goldstar spent time on the dyno and if it didn’t measure up, it got taken apart and built again

This particular DBD was originally a “Roadster”, sometimes called “Western Roadster” which meant a 500CC Goldstar with high, wide bars because Americans were too barbaric to want the pukka version with clip-ons and rearsets. It also had a slightly less impossible first gear ratio and a slightly less nutty cam. but it still had the huge Amal GP carburetor, huge intake port, big aluminum fins, produced the same peak horsepower, and made the same top speed. It was just a tiny bit easier to ride. Don’t expect a miracle, it’s still brutal. “Roadster” meant the original headlight mounts were solid sleeves, the handlebars were high and wide, and I couldn’t wait to take all that crap off and replace them with clip-ons and proper skeleton light brackets. I was going to do rearsets, but discovered after riding it a bit that the stock footpegs felt quite nice and kept the weight off my shoulders. I might get a little lower over the tank with proper rearsets but I was in my 60’s when I started working on this bike, so my body didn’t really want to bend into something my 25-year-old self might have thought was cool. Most Goldstar Clubmans have silver tanks with chrome sides. I briefly considered painting the tank, but it looks too good as it is, and it’s an original tank. Repainting an original tank that already looks good just to change the color is just plain wrong.

a

a

My BSA Goldstar Roadster/Clubman as it looked rolled out of my shop with the dust cover removed for the first time in years. Not bad, but it’s going to take some work to get it ready for sale.

There are a few mechanical differences between a Goldstar Roadster and a Clubman, some of them are desirable in a bike intended to actually be ridden. All DBD Goldstar share the same gear case, but the internals vary widely depending on the use the purchaser intended. This link is to an authoritative page on gearboxes and ratios: http://stevenott.com/gearing.htm. I think the SC T gearbox was used on the roadsters to provide a more practical road vehicle (emphasis on “more” as a relative term). The gearbox ratios were chosen for scrambler (off-road) bikes and it is a close-ratio gearbox with lower gearing in the first three gears and a larger jump to 4th. The final gearing is the same for all Goldstars. They will go just as fast, you simply don’t need to slip the clutch quite as much to get rolling. I know that sounds crazy, but a Goldstar Cataline, a 1959 dirt bike, will go well over 100 mph. I have one. It’s insane.

The most collectible Goldstar transmission is the RR T2 as fitted to the more serious road racing Clubmans. It’s a super-close ratio gearbox so the racer can keep the engine at the optimum RPM at more places on a racetrack. Those of you with an understanding of transmissions and math might wonder “if they all have the same final drive ratio how can the RR T2 be a closer ratio gearbox?” Simple–make first gear super tall. The RR T2 has a first gear ratio of 1.7545/1. The end result is virtually undrivable on the street. With the RR T2 you could certainly use a couple of stout lads following you around, pushing you to get rolling, and you still have to slip the clutch until you are going about 30MPH. You can get well above 60 in first gear without approaching the redline. It’s collectible because it’s rare and super racy. But I doubt anyone drives one, even to Starbucks.

Both the RR T2 and the SC T have needle bearings instead of bushings (the T2 has more). The remaining differences between the bikes are essentially cosmetic–rearsets and clip-ons, a different headlight bracket, and tank color. This one is engine number DBD.34.GS.3346, frame number CB32.3410 and transmission SC T. The engine and frame numbers are consistent with a 1956 BSA Goldstar. As far as I can tell from looking at the available registry information (https://www.bsagoldstarownersclub.com/engine-frame-numbers-by-year/) this is the original engine, and transmission that came with this frame. Essentially a “numbers matching” motorcycle, though BSA numbers didn’t actually match until 1969. The numbers and letters are meaningful. DBD means this is a single-cylinder motorcycle with the “new” head (bigger port and intake valve, better oiling to the rocker arms). The .34 means it’s 500CC. The last 4 numbers are the sequence numbers for that year. In 1956 the sequence started with 2001 which you might think means this is the 1345th Goldstar built that year. But it probably isn’t, there are a lot of oddities in the numbering system. .

I’ve created a PDF of the page referenced above in case the website goes dark.

I bought this bike and a BSA Goldstar Catalina from a guy in Washington State. I had big plans for both bikes and went fairly far along the path with this Roadster. The Catalina I didn’t touch, other than putting a set of new Trials Universal tires on it. That was about twenty years ago. I rode it on fire roads a few times. It kind of scared the shit out of me. I’m used to racing big British singles off-road. My first real desert sled was a Matchless G80CS, a 500cc bike that looks somewhat similar. the Matchless did what I wanted it to do, the BSA Catalina does what it wants to do, and generally, that means creeping up in speed until you realize how fast everything is coming at you. The tires still look brand new, but they are not. Neither are the tires on this Clubman, though they look pretty spiffy. The rear tire was flat, so I put in a new Michelin tube. I don’t remember why I chose the tires I did. The rear tire is an Avon 100/90 V19 Super Venom. The front is a Dunlop K90. They both look new. If I were keeping the bike, I’d ride with them, but I’d keep an eye on them. Old rubber sometimes is fine, and oftentimes it isn’t.

I have fork covers and a new switch on the way. The existing one works fine, but it’s missing the secondary support and detent. New ones are made in India, so I’ll check out what shows up and replace it if the quality is good. These switches look primitive even for 1959, but they are certainly strongly made out of big chunks of brass. I need to disassemble the front end anyway to arc in the brakes (again–I did it twenty or so years ago), check the fork seals, and the damper operation. It feels bouncy. I debated between gaiters (practical) and the original spring covers (beautiful). Spring covers won.

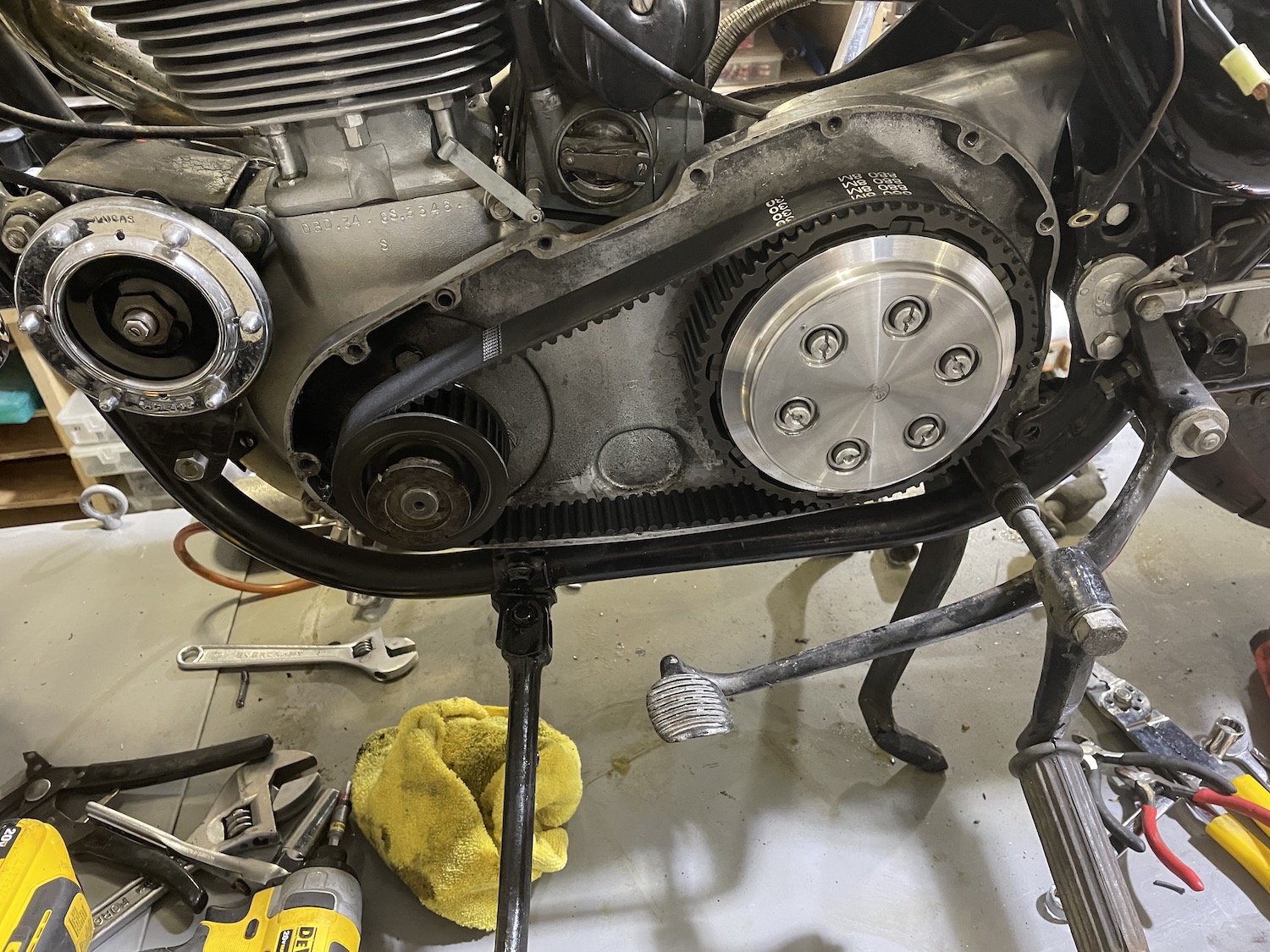

As mentioned previously, Goldstars are geared tall, very tall–you can break the speed limit in first gear before you hit the red line. They are intended to go fast. They only have a four-speed transmission, the horsepower peak(42hp) is at 6500 rpm and the redline is 7000 RPM. Torquey motor, low revs, gear it high. Some wag called the ratios fourth, higher fourth, much higher fourth, and ridiculous fourth. That means you have to slip the clutch to take off in first. In fact, you slip it to at least 25 mph, even with the SC T gearbox, which has a more reasonable first gear ratio of 2.3438-1. The stock clutch can’t take it–not for long. I know purists will say the stock clutch is fine, and they go on and on about proper this and original that. I get it, and I understand why you’d want everything the way it was in 1959. Otherwise, why bother with some beautiful old thing like this. But my intention was to ride it, not just look at it. So it needed a better clutch. Yes, of course, I still have the original clutch, the bearings and races–in fact, I have all the parts I took off, including the original roadster handlebars. I also have the special tool for torquing the upgraded clutch hub. The new owner gets all that of course.

I fitted the best upgrade I could find: an NEB belt drive and dry clutch. Yes, expensive, but the good stuff generally is. It’s progressive, smooth, and silent. If I were keeping the bike, I’d ventilate the primary cover to make sure any oil that got past the seals didn’t wind up on the belt or the clutch, But I’ll leave that to the next owner. The serious racers used to run these bikes without a primary cover. Just a little plate of tin to keep their feet out of the spinning parts. My VR880 Sprint Norton Commando also has a belt primary drive, and it’s been flawless. While I was at it, I replaced the primary cover screws with stainless Allen screws. Again, the anoraks won’t approve. They love their cheese-headed screws. There are plenty of them on the bike, and I’m sure someone stocks them. You can get anything for a Goldstar–just don’t be shocked by the price. Heck, you can buy a complete stock motor from ABSAF in the Netherlands. I briefly considered it for this bike but decided it wasn’t necessary, the engine runs very well, and all the parts I could check without splitting the crankcase had clearances well in spec. I didn’t plan to vintage race it, just ride it. I also replaced the kickstarter pawl. It still worked fine but it showed wear.

The belt drive is nice–chain-driven primary drives are one of the reasons there aren’t many used primary drive covers available. If the chain gets out of adjustment and hops off the sprocket it often busts the case. The belt drive is silent and needs no adjustment other than making certain it does not get too tight. With the engine cold the quick check is to twist the belt in the middle of the run. A properly adjusted belt can almost be twisted 90 degrees. This one was a little tight, so I carefully adjusted it.

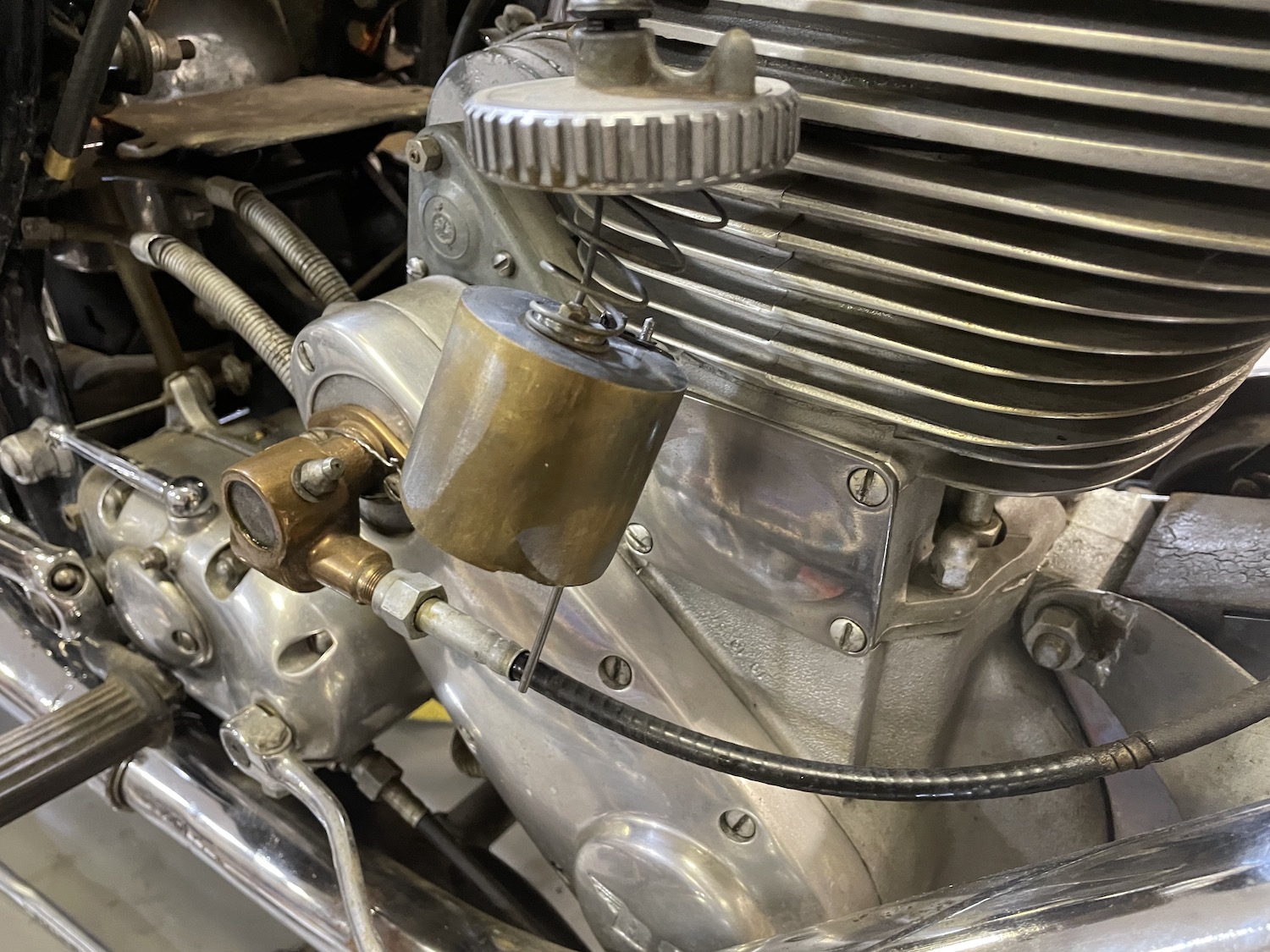

The carburetor is an Amal GP carb. Since it’s been sitting so long, I tore down the entire fuel system. Disassembled and cleaned the petcocks, replaced all the fuel lines, disassembled and cleaned the carb. The Amal GP carb has no idle. It’s one of the few motorcycles that actually has to have the throttle blipped at stoplights. I think the tradition of constantly blipping the throttle may have originated with Goldstars. Mechanics have developed several modifications that enable an idle adjustment, but I elected to leave this stock. Many people fit later Amal carbs or carbs that look a bit like Amals. Some people even replace the carb with a Mikuni or a modern flat slide carb. The Amal GP carb on this bike is in good condition except for the somewhat skanky-looking slide. Replacement slides are available, as are new Amal GP carbs, but even though the hard chrome is worn off and the slide looks a bit dodgy, it slides smoothly in the bore and doesn’t rattle or leak. If the new owner decides to ride this thing often I’d recommend a new slide and an air cleaner. There’s no point in replacing the slide if you keep that lovely open velocity stack.

What a glorious motor this is. Cheese-headed screws actually torque better than Phillips as long as the screwdriver you use isn’t worn and fits the slot perfectly. Phillips screws are designed for fast assembly with automatic tools. Cheese head screws must be done up by hand.

The tank shows some light surface rust inside, but the metal is sound. My borescope shows plenty of surface rust but no pits.

The vent and cap could use some attention.

This side of the tank shows competent dent removal by hammering around the periphery of the dent. Old school, but it works if the practitioner is careful. This is well done.

This side shows a shallow dent and a chrome chip. And someone used a cleaner or scrubber that was too abrasive that scratched the chrome a bit. I could fix this, I’ve become reasonably competent with paintless dent removal tools and this is an easy one–no crease, no buckling, and shallow enough that there is limited stretching. But no. it’s there. If I did that I’d be stripping the tank, re-chroming the panels, and painting it silver. I’m not going there. This tank is original–1956. I’m not going to tart it up.

One petcock had a screw for a handle. I dressed it up a little by threading a piece of brake line to cover the screw, and then I silver-soldered the whole thing in place. I disassembled the petcocks, polished the bore and plug, and then reseated the brass plug with fine valve grinding compound. The end result probably works better than when they were new.

Replacement petcocks are available, but they are in a different style, and they come from India. Some of the Indian bits are quite good, but it’s hard to know what you’re going to get. Since these now work well there isn’t much reason to replace them with petcocks that work differently.

The after picture–I converted the rust with Muriatic acid and then neutralized it with a baking soda solution. I sprayed the inside with WD 40 for protection until the tank is filled. I don’t like coating tanks with goop. Even if users avoid gasoline with alcohol added we don’t control other additives the gas companies stick in gasoline, and some of them dissolve gas tank goop very nicely. I just spray the inside with WD40 to keep the surface rust-free until the tank gets filled with gasoline. Tanks rust when they sit empty. This motorcycle requires premium fuel. It works well with good quality pump fuel, but race gasoline is a bit safer. These engines don’t like detonation.

The tank cap cleared up nicely as well. I don’t try to get every bit of rust off, just the flakes that could cause problems.

Time to rebuild the forks. The original bushing miked out fine, and slid smoothly with no rocking, but new bushings were not too expensive so I bought them to check out the quality. A lot of replacement parts are made in India now, and I’ve heard varied stories about the quality. Wherever these parts were built–the top cover, the seal holder, the bushing, the seals–they all look very good to me and fit perfectly.

New bushings, top cover, springs and seal carrier installed and ready for the lower leg. I cleaned the inside of the fork tubes, added the required 142 cc of fork oil, and put them together. I couldn’t find any specification for the kind and viscosity of the oil in any of my books, and the internet yielded the usual fountain of personal opinion, stupidity, and homebrew notions stated with absolute certainty. But given the primitive damping mechanism, I decided anything reasonably light that doesn’t foam should be good. I used 15 weight BelRay fork oil. My only measuring cup got used for fiberglass resin, so I weighed 142 grams of water in a clear plastic glass and marked the level, then dumped it out and dried it. I didn’t weigh the oil directly since I don’t know the ratio of weight to volume, but a gram of water is more or less 1 cc.

Assembled! They look great. I could have painted the legs, but they look fine and a little patina is a good thing in a 65-year-old motorcycle.

All together and looking spiffy. Of course, the front wheel decided this was a good time to go flat. I’ve ordered another tube. I briefly considered replacing the front tire since it’s certainly aged out, but if I were building this for myself I wouldn’t do that. When the bike is done I’ll ride it for a few days to make sure everything is proper. I’ll do my best not to fall back in love. I know how seductive this thing is. While this isn’t a practical commuter motorcycle it most certainly is the kind of bike that transports you to another time. The sounds, the swoopy handling, the thrust of that surprising engine coming out of a challenging curve–it’s all a bit overwhelming and beautiful. There’s a reason collectors adore the DBD34, and it’s not just how pretty it is.

I’m still waiting for the new headlight switch. That is definitely coming from India. I may just take the compensating arm off to rebuild the switch I’ve got. The decision depends on the quality. The switch I have works fine, but will eventually fail since the arm that compensates for the considerable thrust of the contact springs was removed at some previous time. The arm makes the switch stiff to turn, so it might have been a popular modification. I plan to take the thing apart and apply dielectric grease anyway. The original wiring uses the extra unconnected posts on the switch as binding posts, like a very closely spaced, poorly designed terminal board. I’m not going to do that, and I can’t bring myself to rewire this thing without fuses, so I won’t be using the spare posts. Instead, I’m going to tuck a 6-fuse panel into the headlight cover and protect each circuit. The fuse panel also serves as an excellent covered terminal block. I use connectors with shrinkable waterproof insulators that have low-temperature glue inside them. they never pull out if properly made up. Some modern touches are just too good to pass up. The wiring of these motorcycles couldn’t be more simple, and I appreciate that. I like things that have been simplified as much as they can be–but not at the expense of reliability. I see no reason why the owner should have to drive home in the dark or have the wiring harness burn up because originality was taken a step too far.

Links for light reading:

https://sump-publishing.co.uk/bsa-gold-star.htm

https://www.mecum.com/lots/LV0117-263416/1960-bsa-dbd34-gold-star-clubman/ (this bike sold for $30K in 2017)